Thinking about the ocean requires us to think three dimensionally, and in particular to think in terms of volume. Thinking three dimensionally sits in contrast with traditional Western ways of understanding and documenting space by flattening it through technologies such as maps.

Flattening space into two dimensions makes it easier to draw borders and make claims over territory. Thinking in three dimensions offers challenges to how we document and exert ownership over space, but it more accurately reflects the physical state of the world.

Thinking in three dimensions is still somewhat of a constructed and reduced version of space. The ocean doesn’t just exist in the vertical and horizontal plane, but we could think of it as having spherical spatial qualities with an infinite number of axes. This is a volumetric understanding of space.

Taking this even further, we consider not only the volume but the qualities of volumetric space and spatial mediums such as the ocean. A milieu of may material qualities and meanings.

This volumetric space, alongside spatiality, attempts to capture the ‘reach, instability, force, resistance, incline, depth and matter’1 that collectively characterize the volumetric mediums of ocean, atmosphere, and earth.

The idea of a voluminous ocean, fluid and dynamic, underpins many of the projects being developed by the Collective.

1 Elden, S., 2013. Secure the volume: Vertical geopolitics and the depth of power. Political Geography 34, 45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polgeo.2012.12.009.

Our Geographic Foci

Deep Abyssal Plains

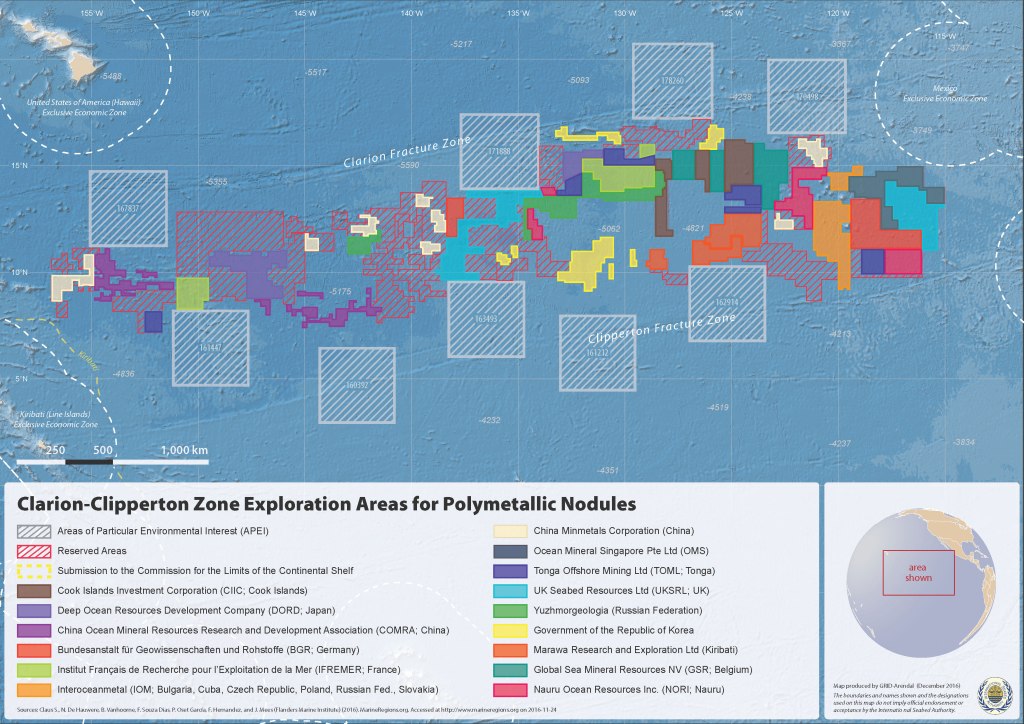

The deepest oceans are under threat of mineral development, perhaps starting in 2026. The seafloor beneath the High Seas, or Areas Beyond National Jurisdiction (ABNJ), are also designated as the Common Heritage of all Humankind. Yet private companies aligned with government sponsors are arguably operating without public consent to these extractive and damaging projects.

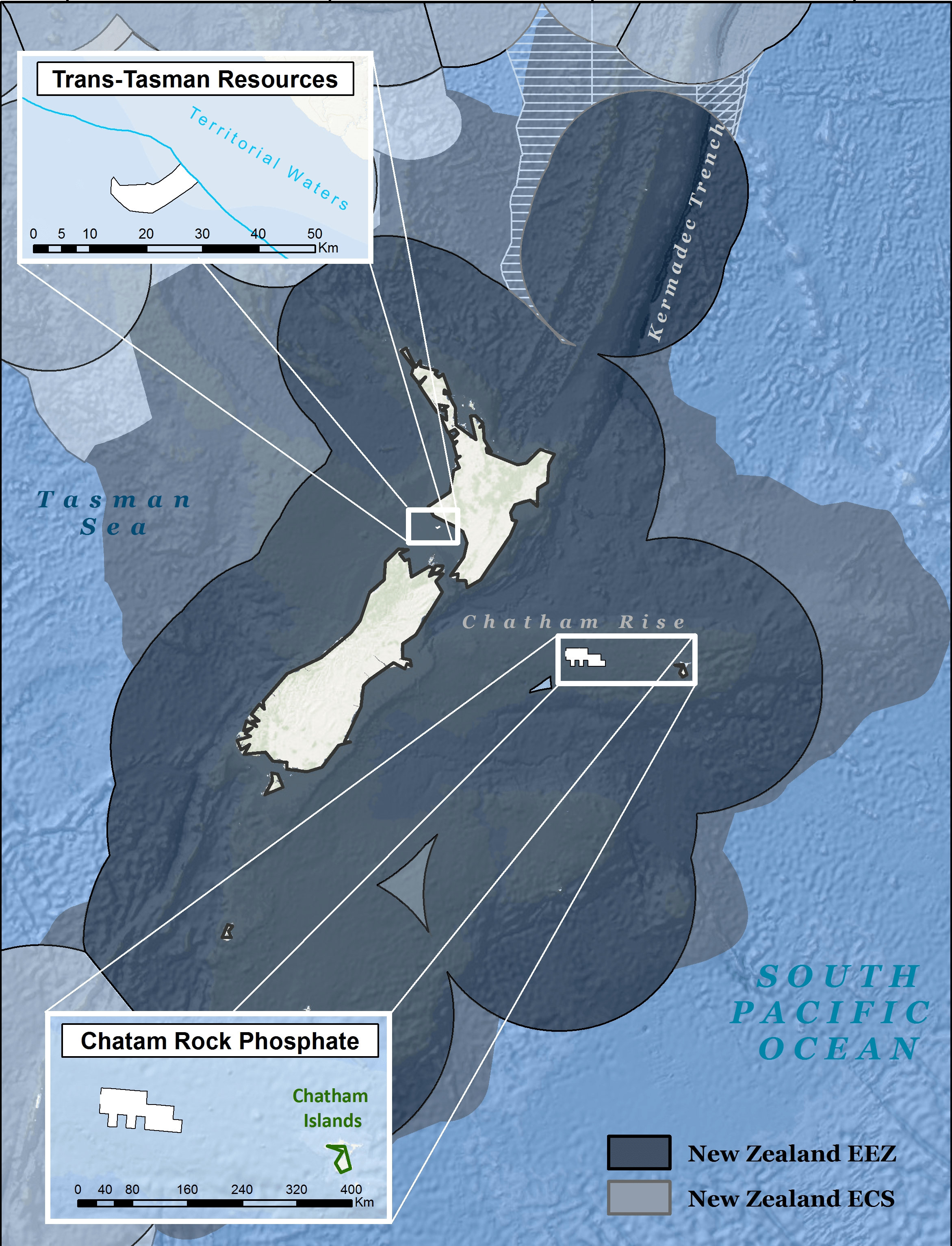

Shallow Seas and Coastal Areas

Many island and coastal countries are considering opening up offshore mining in their coastal waters. Granted jurisdiction by the UN Law of the Sea treaty, countries manage waters up to 200 miles offshore, designated their Exclusive Economic Zones. Nearshore mining tends to story deep concerns over fisheries degradation and water pollution.

Outputs

The oceans provide 99 percent of the Earth’s living space. It is the largest space in our universe known to be inhabited by living organisms. More than 90% of this habitat exists in the deep sea known as the abyss.